Long time, no write. I decided I wanted to remedy this as I was walking to the library, winding through Soho and into Piccadilly. It was a beautiful afternoon, the light golden and diffuse, vellus-hair soft. I have myriad reasons and excuses for my absenteeism, which range from the legitimate to the semi-allowed to the taking-the-piss.

The legitimate: I have a new job – I became a staff writer at a new magazine called The Londoner, and have now just recently been made its editor – in which I am working very hard a lot of the time, and sometimes I simply do not want to look at another computer screen when I am done for the day (which is quite frequently late at night).

The illegitimate: I keep thinking of things to write about, essentially writing them in my head, and then not publishing them; a loss of authorial confidence that's perhaps the result of going once more into an editor role (I am still writing, but now I have one day a week to do this and have to be very disciplined to actually use it). Still, it's very exciting, and I've written some things I'm proud of, particularly this piece about the changing quality of London's street lighting, this mean little article about Moko Museum and this rumination on the Yellow Bittern. But I want to try and publish more consistently on this Substack too – call it a spring resolution – to have something that is uncontrovertibly my own. Perhaps this desire was prompted, to some degree, by watching Claudia Weill’s 1978 film Girlfriends (written by Vicki Polon), which I saw a fortnight ago via my beloved Internet Archive.

A duckling, downy and tender and garrulous, delivered in a ribboned box; a woman and a man, a couple, both naked, kissing in the soft golden light of the giant windows of the loft apartment; a woman, the same woman, slumped in front of unpacked boxes, sobbing to the sound of the radio, pitifully and painfully alone: the images of Girlfriends alternate between close or wide, a push-pull of intimacy and distance, and they function – cinematically and thematically – as snapshots, a Kodak carousel of scenes. Our protagonist, Susan, is a struggling photographer; in one exchange with an editor she hopes to interest in her work, he crops her images, and tells her that she has to “get close… you got to take that lens and put it in their faces”. Later, she wants to hang a close-up in an exhibition, but it’s left out by the curator. The film mirrors this formal conceit: Click! A pregnancy has been announced. Click! The baby is two years old.

Girlfriends is concerned less with development in terms of transformation – the characters change little, really, as the film’s runtime progresses – than with development as enlivenment, enrichment, the outlines of her protagonist (or protagonists, but more on that later) growing sharper, more focused, shadows inked in the evening sun. The film’s plot is, I suppose, a Bildungsroman, in the loosest sense (and also a Künstlerroman?): a young woman, Susan, mid-twenties, hair loose, blouse unironed, is living with her best friend, Anne. Susan is everything Anne is not. She is Jewish, while Anne is pure WASP; a brunette, while Anne is blonde; a photographer, while Anne is a writer; single, while Anne is in a relationship.

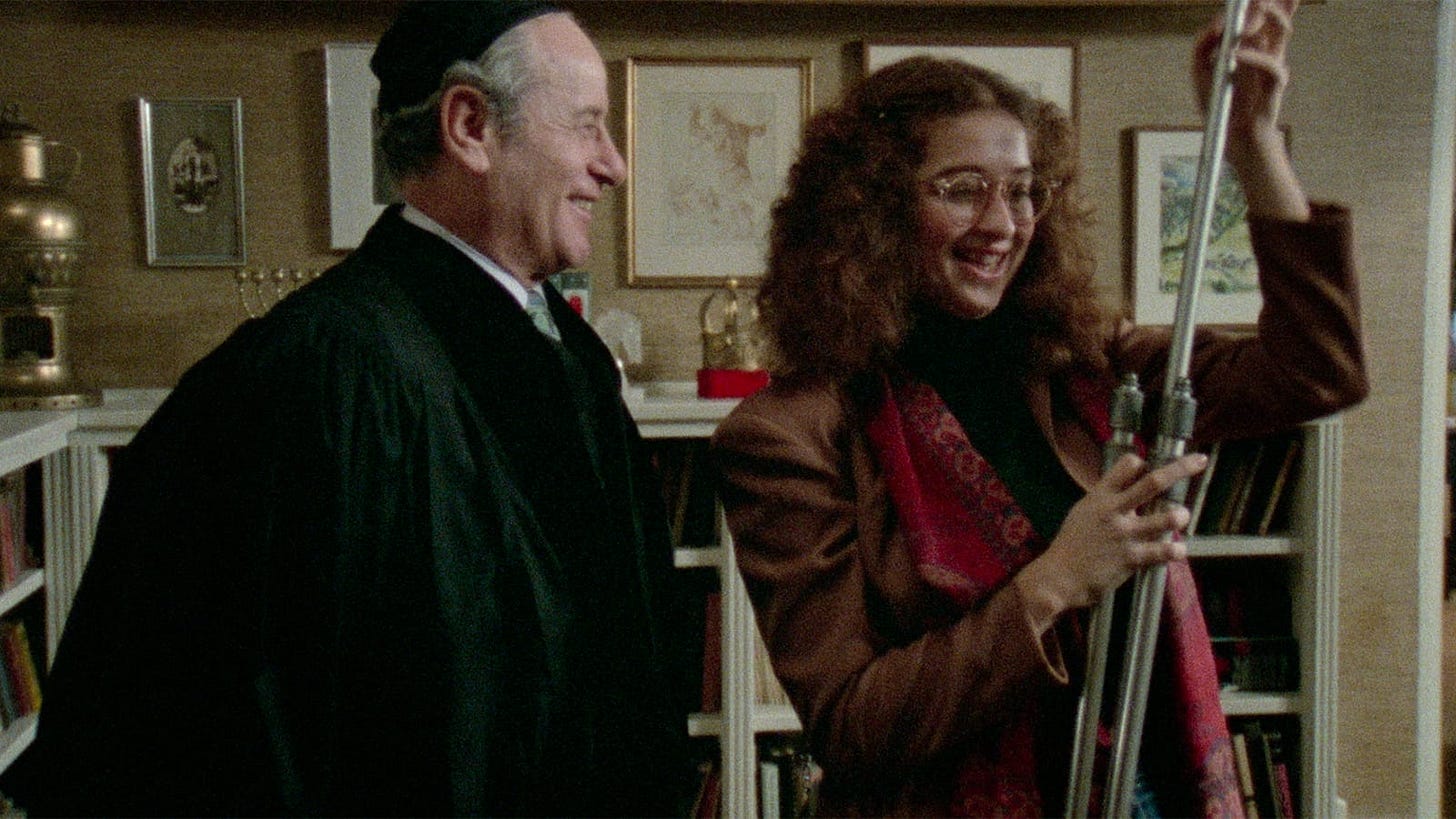

Soon after the film starts, Anne leaves Susan – yes, leaves, with its connotations of romantic abandonment, is correct; multiple characters assume they were lovers – to marry her boyfriend. Susan is heartbroken by this caesura, alone in her new apartment (I admit to feeling a little churlish about sympathising with a character who is sad about living alone in NYC, but such were the 1970s). Her professional life is similarly less than ideal. She longs to be known as something more than a photographer of bar mitzvahs and weddings, trundling around the city with her portfolio under her arm, her prints, like her belongings, perpetually encased in cardboard – only when she lands that coveted exhibition spot does she trade it for a leather option. She briefly contemplates an affair with the rabbi she works with, but ends up in a relationship with Eric (a pre-Spinal Tap Christopher Guest), who she met at a party and, after a few lines of stilted conversation, went home with, an impulse prompted by repeated questions about Anne’s wedding. Initially, Anne wants it to be nothing more than a one-time thing and leaves midway through the night. When they later reunite, Eric asks why: “I was just coming out of a heavy relationship”, she answers. He asks if they were living together, and she nods.

Girlfriends is a very good film, visually and thematically: its anachronisms compellingly fantastical to the contemporary viewer (that apartment! that New York!); its focus on female friendship still rare enough in today’s cinematic landscape to feel significant; its proto-mumblecore sensibilities prescient. It feels tight without feeling wound, meditative without feeling pondering, a film that’s content to let its protagonist and her life encompass the frame, encompass the runtime.

Its success rests on Melanie Mayron’s Susan, her effortless charisma, her egg-yolk smile, rich and golden and pouring forth, her Brooklyn-Jewish old-school New Yawk accent, the way we fall in love with her, as we must, so that by the film’s close it is us who is left, us who is heartbroken. While watching the film, I began to think that Mayron was the most beautiful person I had ever seen on screen (I was genuinely devastated, in a strange, parasocial way, to learn that she had had a nose job a year or after it was made, prompted by watching herself in a TV show). Its weaknesses mostly lie with Anne, who is largely a character in abstract – an idea that half-works, if you view her distance, her primness, as the contrast to Susan’s immediacy, her intimacy. But it doesn’t really work when we’re meant to buy them as friends, when we’re meant to mourn as Susan does when the relationship ends – or at the very least, when we’re meant to understand why Susan is so upset.

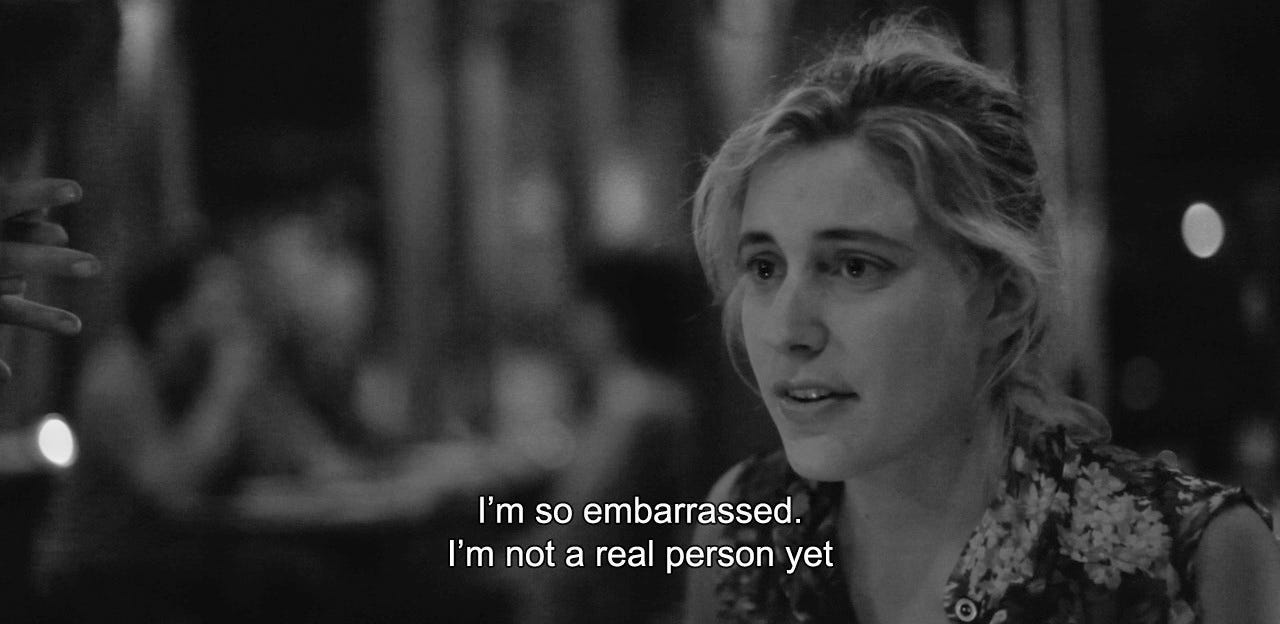

The film to which Girlfriends is always compared, and for good reason, is Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s Frances Ha, which doesn’t simply follow the former’s focus on women in the creative arts attempting to find success, fulfilment, a way to work and be and feel, but also its pacing, its characterisation, almost its script. There’s a slight flip – protagonist Frances is the blonde one, her friend Sophie the brunette – but otherwise the dichotomy remains the same. Frances is the chaotic one, the single one, the one who seems to love more. I say this not to suggest that I think Frances Ha – which has, I’m afraid to say, always been one of my all-time favourite films – is diminished by having watched Girlfriends; in fact, I think it actually deepened my appreciation for it. Everybody on the web says that Gerwig has cited Weill’s film as one of her favourites, a claim I can’t really see any evidence for, but its influence is so direct, so obvious, that it must be the case (there is, similarly, there is a direct through-line from Girlfriends to Lena Dunham’s GIRLS (also my favourite TV show…), which Dunham acknowledged by asking Weill to direct a couple of episodes.

Frances Ha, to my mind, is the better portrayal of friendship; Frances and Sophie’s relationship, while similarly romantic, has the quality of something lived-in, a cotton t-shirt worn thin and soft, almost silken, over the years. But to simply say that there would be no Frances without Girlfriends is to do the earlier film a disservice, to suggest that there is something prototypic about it, something rough-hewn. This isn’t the case: the films, although existing, in many ways, as a call and response, look at the same subject matter through different lenses. Girlfriends is much more effective as an exploration of feminism — both late 1970s and, because we haven’t advanced very far as a society and may have in fact moved backwards, of the present day.

Weill never judges her characters or moralises their predicaments, although Anne’s situation as a wife and mother is fairly obviously stifling and unrewarding, and by the end of the film she hasn’t progressed with her writing, that we can see (from the little we hear, Anne also seems to be a fairly bad writer, which I quite liked — creative expression is necessary for everybody, regardless of talent!). Susan is rewarded with an exhibition and a handsome boyfriend, who brings her the duckling as a present for her opening and, although neither of these things are quite as she envisaged them, they are manifestations of the possibilities open to her, of the way that life can expand, fill streets and boulevards and studio-high windows with white-gold morning light, rather than narrow, as it seems to have done for Anne, whose little cottage upstate has small windows, quaint little bisected panes. At the end of the film, Anne has an abortion, one of the only instances I can recall in film or TV of a woman with a loving husband and child still electing to have one.

Frances, then, is less concerned with feminism, in that breezy, flung-hand way of the early-to-mid noughties film scene. Its decision to sideline (and almost entirely ignore) Frances’ romantic relationships with men, in contrast with Girlfriends’ focus on Susan’s romantic and sexual entanglements, allows it to cannily abdicate from an exploration of heterosexual power dynamics. Instead, its lens is on class, which it articulates in an incredibly skilful way that it doesn’t get enough explicit credit for, despite this being, I believe, the reason why so many young women adore it (Greta Gerwig, to my mind, made/written two excellent films about class – Frances Ha and Ladybird – making her decision to sell out to the Hollywood IP industrial complex even more dispiriting and artistically stultifying).

The politics of class influence Girlfriends, sure, but fundamentally it is a film set in a time when a struggling female artist could afford to live in Manhattan on her own, a circumstance that is now so far from reach as to feel whimsical, even comedic in its preposterousness. Frances, in contrast, is at its best an examination of what happens when youd begin to realise that your peers are not, as you thought, dealing with the same financial struggles as you are, that their supposed money troubles are something that they can shed, slip off like a jacket come springtime. They get to feel the sun on their bare arms.

The character of Frances is the first great manifestation of the over-educated, financially insecure millennial middle class: “You're not poor. Saying that is an insult to poor people”, her friend and housemate Benji tells her when she pronounces herself so. He’s right, in that Frances isn’t poor in the way of the kitchen sink drama, in the way of the poverty line, in the way of the food stamp. But there isn’t really a neat word for what she is – financially depressed? fiscally lacking? – and she’s hit the age where she’s finding out that she’s not quite good enough, or rich enough, to sustain the career or lifestyle she’d expected.

But Benji is rich, the kind of person who can afford a huge warehouse-style loft without having a job, who has an Eames chair (“The boys just have good eyes. They find stuff all the time,” pleads Frances in wilful, self-sustained ignorance, when Sophie describes their “total rich-kid apartment), who can get fired and change careers and spend and spend and spend without thinking. There’s a false bonhomie – neither of us are billionaires and neither of us are poor, so we’re pretty much the same – that feels acutely and painfully familiar. But the lower middle class is not the upper middle class, and Frances is much, much closer to poor than her friend is. “I thought we were both broke!”, she tells him after he talks about buying “three pairs of very rare Ray Bans”. “I caved and finally took a loan from my step-dad. Bastard,” he replies. When Frances calls her parents from her waitressing job, they tell her that they’re sorry they can’t afford to help her out. Her other housemate, Lev, played by an early career Adam Driver (the connoisseur’s choice) demands more money than agreed, despite being unfathomably rich. (Lev: Oh, can you leave that rent check for me? Frances: “Yeah, yeah, sorry. I’ll put it on your desk. It’s for $950? Lev: Nope. $1200.) Money isn’t significant to these people, of course, until it is; friendship is absolute, until it isn’t.

At the end of both Girlfriends and Frances, both women have achieved the independent success they wanted, though neither has entirely found it in the way they expected. In the former, Susan has left her exhibition to drive upstate to see Anne post-abortion. She isn’t sure whether to move in with Eric; “I’m afraid of being left”, she says. But, surely, there’s more to it than this – after all, Susan doesn’t get to include a piece she wants in the show because she’s too busy fighting with Eric to approve the final hang. To move in with him, she knows, is to become beholden to somebody else, to sacrifice not just personal but artistic autonomy; look at Anne, fleeing her husband and child to secretly have her abortion and claim back some semblance of independence. In the latter, Frances has had to accept that her dream of being a dancer is not feasible, and has instead taken a job in the office of her dance school and become a choreographer. She can now rent her own apartment, under her own name (that she could afford an apartment alone on this wage seems vaguely implausible, but let’s go with it – early 2010s NYC is a different country). Both films end with parallel glances between our protagonists and their female soul mates, a look that registers the intimacy between them, and the distance.

Thanks for reading,

H x

Mostly unrelated

Melanie Mayron’s mannerisms – particularly her smile – remind me so much of another actress, but I can’t think who. Any suggestions?

I wrote my postgrad dissertation on 1970s American female novelists, and so feel a least relatively qualified to recommend Renata Adler’s Speedboat and Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights (my favourite book) as good accompaniments to Girlfriends.

Claudia Weill directed one more film, It's My Turn, which looks far more conventional – it was recut, without her consent, by the film’s producer, whose bullying made her leave feature films altogether. A really depressing and probably very common story!

The soup scene of GIRLS, aka one of the most transcendent scenes of all time (I am utterly serious when I say that Lena should’ve won the Emmy AND the Golden Globe for this).

These antique French oyster plates that I’ve become obsessed with (I can say with certainty that I would never use them. But isn’t it nice to pretend?)

I’m very excited about Philippa Snow’s new book. I think she’s very easily one of the best critics currently working, in that I’m-glad-to-exist-at-the-same-time-as-this-greatness kinda way. Start here, then read everything else.

I’m currently working my way through War & Peace, which is fantastic, although I did have a short break to reread some Didion. I bought a cheap two-book edition version of W&P, and I’d recommend it. Why don’t publishers do that anymore? I hate lugging around what can only be described as “tomes”.

The Ed Atkins exhibition at Tate is phenomenal. Didn’t really know anything about it going in and was kind of unconvinced by the press release, but by around the third room thought it was the best thing I’d seen so far this year.

Loved your comparative notes on Girlfriends and Frances Ha, Hannah! I, too, recently watched Girlfriends and fell completely in love with it. I think Melanie Mayron looks a bit like Elaine Benes?!

Wrote a bit about Girlfriends and Nicole Holofcener's Walking and Talking on my substack: https://scurfofyesterday.substack.com/p/how-should-a-person-be

I enjoyed reading this!

Regarding class differences, your piece made me think about Sophie's background, which I'd never thought about much before. I never got the sense that she came from money, but she definitely has different class aspirations than Frances: Sophie works at a prim and proper publisher, dreams of living in Tribeca, and is attracted to (or at least wants to marry) finance guys. Frances thought she had a sister-in-arms to go through the whole NYC boho life together, but for Sophie, it was always just a phase.

And Frances, for all her seeming frivolity, turns out to actually be quite dedicated to her art, even to the point where she's willing to swallow her pride and take lesser roles to continue to be a part of that world.